이번달 중순 상하이에 열린 토론회에서 중국에서 가장 상업적으로 성공한 영화감독 펑샤오강은, 중국 영화산업이 5∼10년 내 세계에서 두 번째로 큰 규모가 될 거라 예측했다. 펑 감독은 얼마 전에 장쯔이가 출연한 셰익스피어의 <햄릿>을 각색한 1500만달러짜리 <야연>을 마무리했다. 이 영화는 9월에 중국에서 개봉하기 전에 베니스영화제에서 월드 프리미어를 가질 계획이다.

2005년에는 장편영화 260편이 베이징영화청에서 배급허가를 받았다. 이 수치는 전년대비 20% 증가한 것이다. 일부는 홍콩과의 공동제작물이었지만 그럼에도 단편, 텔레비전용 영화, 다큐멘터리, 그리고 일명 ‘지하전영’ 영화를 제외한 이 수치는 놀랍다. 그러나 260편 중 유료 관객을 위한 영화관에서 상영될 영화는 몇편 안 된다. 중국은 1인당 극장 수가 적은데다가 외국영화 쿼터는 있지만 국내영화에는 상영쿼터를 주지 않기 때문이다.

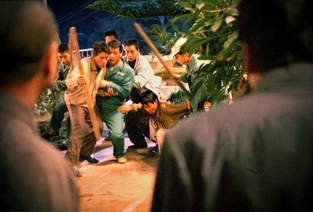

6월에 개최된 상하이국제영화제는 60편의 최근 중국 장편을 상영했는데, 지난 18개월에 걸쳐 제작된 가장 덜 흥미로운 본토영화들이 주를 이뤘다. 행복한 소수인종, 모범시민에 대한 전기영화, 그리고 사회의식에 대한 영화들이 그 중 몇몇 예다. 이 영화제에서 가장 흥미로운 중국영화는 초보평의 유쾌하게 통속적인 <트러블메이커>이었을 것이다. 초보평의 영화가 나중에 두개의 작은 상을 타갔지만, 주중 저녁에 열린 한번의 상영회는 7장의 티켓밖에 팔지 못했다.

중국영화는 국내 극장개봉의 기회가 거의 없는데다 해외판매는 가느다란 희망밖에 없기 때문에, 감독들은 유일하게 보증된 관객을 위해 영화를 만드는 경향이 있다. 그 관객은 자기 자신들이다. 정말 소수의 감독만이 관객이 접근할 만한 영화를 만드는 데 관심을 둔다. 그러나 이런 감독들은 제작비를 모으는 데 아무런 문제가 없는 반면, 배급의 기회를 잡기란 훨씬 어렵다. 첸다밍, 장이바이, 지에동은 같은 감독들은 정치적인 검열보다는 보수적인 극장 운영자들 때문에 극장에서 영화를 상영하는 데 어려움을 겪어왔다.

중국영화는 세계에게 (그리고 자국에게도) 자신들의 영화를 소개할 수 있는 행사를 하나도 갖고 있지 못하다. 1980년대 아주 짧은 기간 동안 홍콩국제영화제가 이른바 ‘5세대’의 부상을 위한 관문으로서의 그 역할을 수행했다. 현대 본토 중국영화에 초점을 맞춤에도 불구하고 올해 영화제는 중국 장편 극영화 프리미어를 단 한편도 갖지 못했다. 영화제 프로그램에 있는 영화들은 이미 부산국제영화제를 비롯한 전세계의 다른 행사들에서 소개된 것들이었다. 20여년 동안 중국에서 가장 두드러진 영화들은 유럽 영화제들에서 프리미어를 가졌다. 한국은 이제 동일한 방식을 따라가고 있다. 해외 게스트들은 더이상 한국영화를 보기 위해 부산영화제에 오지 않는다. 발견하기 위해 오는 것은 고사하고 말이다. 지난 5월 칸영화제에서 이루어진 봉준호의 <괴물> 월드 프리미어뿐만 아니라, 칸영화제 참석자들은 마켓에서 20편 이상의 한국영화를 볼 수 있었다. 그리고 홍상수와 임상수의 가장 최근 영화들은 베니스에서 프리미어할 가능성이 높다. 두드러지게 유명한 한국영화가 부산에서 프리미어하는 것은 타이밍상 우연의 일치가 될 뿐이리라.

부산영화제는 이런 사실을 인식하고 아시아영화의 경쟁부문인 뉴커런츠 부문 출품작들에게 월드 프리미어 조건을 점점 더 강력하게 요구하면서 경쟁이 심한 가을 시즌 영화제 환경에 적응하고 있다. 불리한 결과를 낼 수 있는 도박일지도 모르지만, 10회를 넘긴 영화제를 강화할 수 있는 힘이 될 수도 있으며, 해외 게스트들의 관심을 중국을 포함한 아시아영화에 돌리는 데 일조할 수도 있을 것이다.

At a panel discussion in Shanghai last week, China's most commercially-successful film director, Feng Xiaogang, predicted that the mainland film industry will become the second largest in the world within five to ten years. Feng has just completed his latest film, The Banquet, a US$15m adaptation of Shakespeare's Hamlet starring Zhang Ziyi. It's tipped for a world premiere at the Venice Film Festival before opening across several Chinese territories in September.

In 2005, 260 completed feature films received a distribution licence from the Film Bureau in Beijing, an increase of 20% on the previous year. A portion of these were Hong Kong co-productions, but the still astonishing number excludes shorts, television movies, documentaries and "underground" cinema. Few of these 260 films, however, will ever be projected in a cinema for a paying audience as China has so few movie theatres per capita and only a quota for foreign films, not local ones.

June's Shanghai International Film Festival presented 60 recent Chinese features, dominated by some of the least interesting mainland films produced over the past eighteen months. These include films about happy minority races, biopics of model citizens and films about social consciousness. Perhaps the most exciting Chinese film at the festival was Cao Baoping's joyously vulgar Trouble Makers. While Cao's film went on to win two minor prizes, it sold only seven tickets to the public at its single screening on a midweek evening.

Since Chinese films have little chance of domestic theatrical release and slim hope for overseas sales, directors have had a tendency to make films for their only guaranteed audiences: themselves. Just a handful of directors are interested in making accessible films for audiences. But while these directors have no problems raising finance, distribution is more elusive. Directors such as Chen Daming, Zhang Yibai and Xie Dong have had difficulties getting their films into cinemas because of conservative theater operators rather than any political censorship.

Chinese cinema has no single event to introduce its cinema to the world (or to itself). For a brief period in the 1980s, the Hong Kong International Film Festival served that purpose, acting as a gateway for the emergence of the so-called Fifth Generation. Despite a focus on contemporary mainland cinema, this year's edition of the festival was unable to premiere a single narrative feature from China. The films in their program had already been introduced at other events around the world, including the Pusan International Film Festival.

For almost twenty years, China's highest profile films have received their premieres at European festivals. South Korea is now following the same pattern. Overseas guests no longer visit Pusan to watch - let alone discover - Korean cinema. In May, in addition to the world premiere of Bong Joon-ho's The Host, Cannes attendees could catch over twenty different Korean films in the market. The latest films from Hong Sang-soo and Im Sang-soo are likely to premiere at Venice. Any high-profile Korean premieres at Pusan will be an accident of timing.

Pusan is aware of this and is adapting to a more competitive fall festival environment by becoming more demanding of world premieres in its competitive New Currents section for Asian films. It's a gamble that could backfire, but it could also strengthen the festival as it enters its second decade and help direct the attention of its international guests toward Asian cinema, including that of China.